现代c++编程

#include <print>

int main() {

std::println("Hello world!");

}

编译

c++ -std=c++23 -Wall -Werror first.cpp -o first

运行

./first

编译和运行

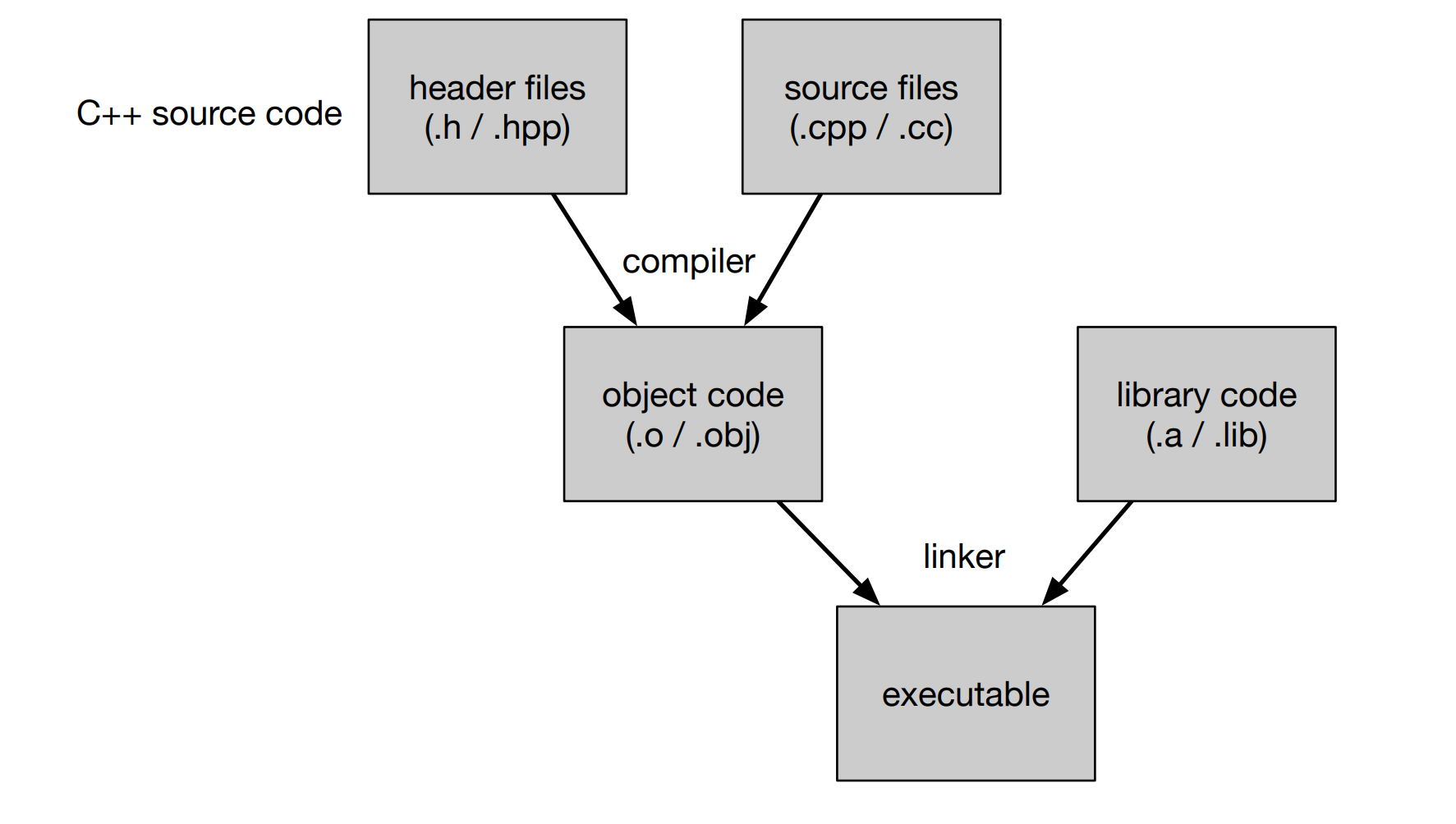

首先被编译成object code 然后linker会link一些库最后编程可执行文件

- translation unit: input of compiler

- object code is the output of compiler

#includeis done vis the preprocessor (literally included = long compilation time)- compiler uses the declaration to know the signature of object, not resolve external thing

- linker check these symbols

头文件和源文件

- declarations in header files

- definitions in source files

ODR

- all object have at most one definition in any translation unit

- all object that are used have exactly one definitions

Head guards

#ifdef H_HEAD

#define H_HEAD

#endif

或者

#pragma once

modules (doesn't work yet)

定义module

export module sayHello;

import <print>;

export void sayHello() {

std::println("Hello World!");

}

使用

import sayHello;

int main() {

sayHello();

}

CMake

CMakeLists.txt

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.27)

project(exampleProject LANGUAGES CXX)

add_executable(exampleProject main.cpp)

cmake_minimum_requiredrequire at least a versionprojectdefine a project with nameadd_executablebuild executable with name and source fileadd_librarydefine a librarytarget_include_directories(myProgram PUBLIC inc)where to look for include files for the target “myProgram”target_link_libraries(myProgram PUBLIC myLibrary)which libraries to add to target “myProgram”

C++ Basic

Types and built-in types

- static type safety

a program that violates type safety will not compile, compiler report violation

- dynamic type safety

if a program violates type safety it will be detected at run-time

C++ is neither statically nor dynamically type safe!

TYPE variablename{initializer};

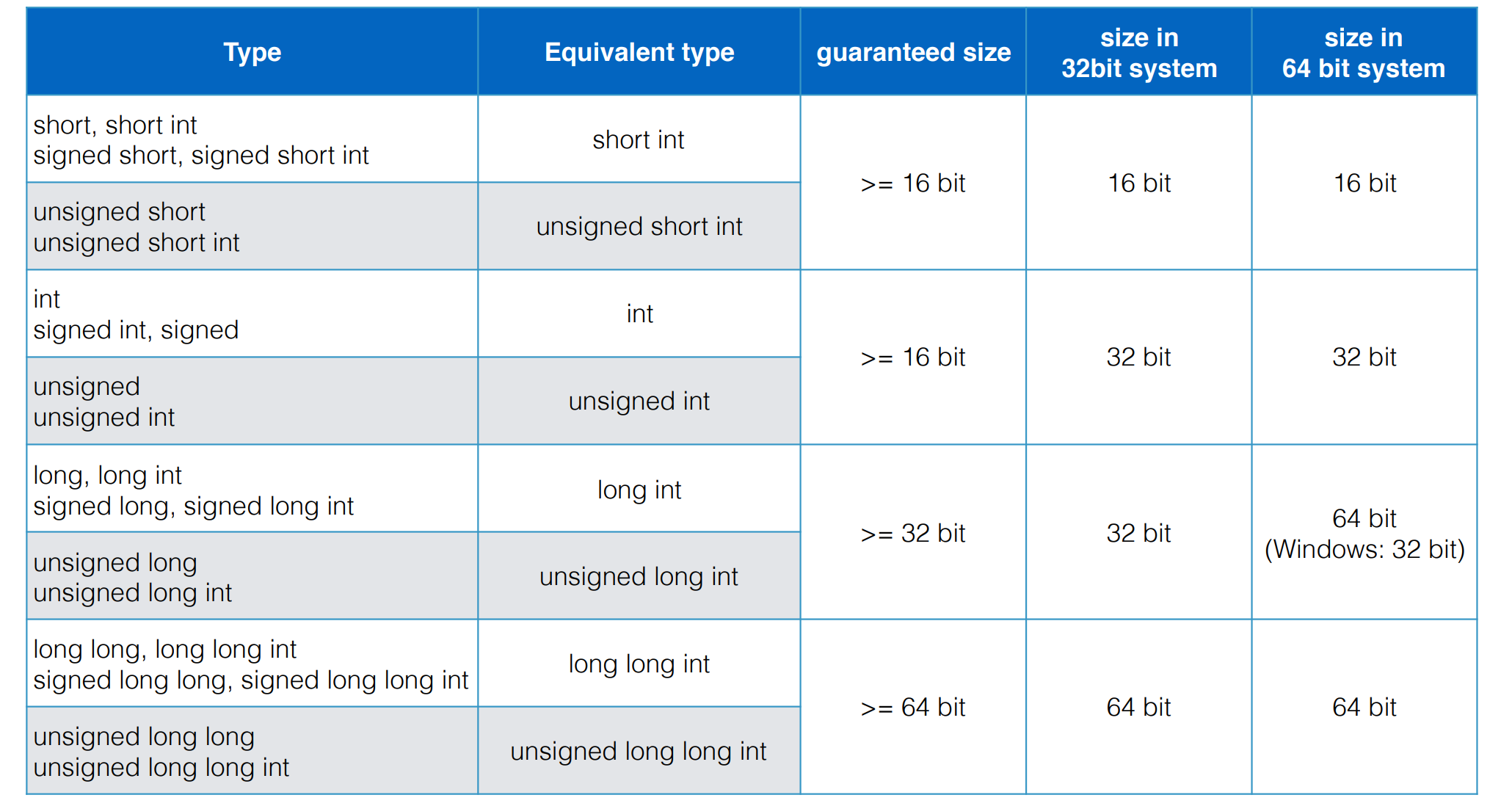

Integer literal

- decimal:

42 - octal(base 8):

052 - hex:

0x42 1'000'000'000'000ull

careful 0xffff maybe -1 or 65536

cout << 0xffff << endl; // 65536

std::ptrdiff_t

const std::size_t N = 10;

int* a = new int[N];

int* end = a + N;

for (std::ptrdiff_t i = N; i > 0; --i)

std::cout << (*(end - i) = i) << ' ';

std::cout << '\n';

delete[] a;

- double (64bit): approx. 15 digits

-

long double (64-128bit): approx. 19 digits

1.0l -

float128_t

Initialization

safe: variableName{}

unsafe: variableName = or variableName()

the unsafe version may do (silent) implicit conversions

local variables are usually not default-initialized, this can lead to undefined behavior when accessing an uninitialized variable

const

const T

a const object is considered immutable and cannot be modified

extern int errorNumber; declare, no definition

using Cmplx = std::complex;

float sqrt(float); declares the function sqrt, taking a float as argument, returning a float, no definition!

std::vector<int> v1{99}; // v1 is a vector of 1 element

// with value 99

std::vector<int> v2(99); // v2 is a vector of 99 elemen

std::vector<std::string> v1{"hello"};

// v1 is a vector with 1 element with value "hello"

std::vector<std::string> v2("hello");

// ERROR: no constructor of vector accepts a string literal

std::complex<double> z1(0, 1); // uses constructor

std::complex<double> z2{}; // uses constructor,

// default value {0,0}

std::complex<double> z3(); // function declaration!

std::vector<double> v1{10, 3.3}; // list constructor

std::vector<double> v2(10, 3.3); // constructor, v has 10 elements set to 3.3

int x{}; // x == 0

double d{}; // d == 0.0

std::vector<int> v{}; // v is the empty vector

std::string s{}; // s == ""

Type Alias

typedef int myNewInt; // equivalent to using myNewInt = int

Scope

int x{0}; // global x

void f1(int y) { // y local to function f1

int x; // local x that hides global x

x = 1; // assign to local x

{

int x; // hides the first local x

x = 2; // assign to second local x

}

x = 3; // assign to first local x

y = 2; // assign to local y

::x = 4; // assign to global x

}

int y = x; // assigns global x to y (also global)

Lifetime

The lifetime of an object

- starts when its constructor completes

- ends when its destructor starts executing

using an object outside its lifetime leads to undefined behavior!

storage duration: which begins when its memory is allocated and ends when its memory is deallocated, the lifetime of an object never exceeds its storage duration

-

automaticallocated at beginning of scope, deallocated when it goes out of scope -

static: allocated when program starts, lives until end of program -

dynamic: allocation and deallocation is handled manually (see later) (usingnew, delete) -

thread-local: allocated when thread starts, deallocated automatically when thread ends; each thread gets its own copy

Auto

#include <print>

#include <memory>

#include <boost/type_index.hpp>

using namespace boost::typeindex;

int main() {

auto a = {13, 14};

auto u{std::make_unique<int>()};

std::println("Type a: {}", type_id_with_cvr<decltype(a)>().pretty_name());

std::println("Type u: {}", type_id_with_cvr<decltype(u)>().pretty_name());

}

Array and Vector

#include <array>

#include <print>

int main() {

std::array<int, 10> a{}; // array of 10 int, default initialized

std::array<float, 3> b{0.0, 1.1, 2.2}; // array of 3 float

for (unsigned i = 0; i < a.size(); ++i)

a[i] = i + 1; // no bounds checking

for (auto i : b) // loop over all elements of b

std::println("{}", i);

a.at(11) = 5; // run-time error: out_of_range exception

}

- Do not use:

int a[10] = {};

float b[3] = {0.0, 1.1, 2.2};

Not-fixed size array: vector

Loop

#include <print>

#include <format>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::vector<int> a{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}; // initializer list

for (unsigned i = 0; i < 5; ++i) // regular for loop

a.push_back(i + 10);

for (const auto& e : a) // range for loop

std::print("{}, ", e);

std::println("");

for (auto i : {47, 11, 3}) // range for loop

std::print("{}, ", i);

}

lvalue and rvalue

lvalue

- lvalues that refer to the identity of an object, modifiable lvalues can be used on left-hand side of assignment

rvalue

- rvalues that refer to the value of an object, lvalues and rvalues can be used on right-hand side of assignment

Increment

- prefix variants increment/decrement the value of an object and return a reference to the result

- postfix variants create a copy of an object, increment/decrement the value of the original object, and return the unchanged copy

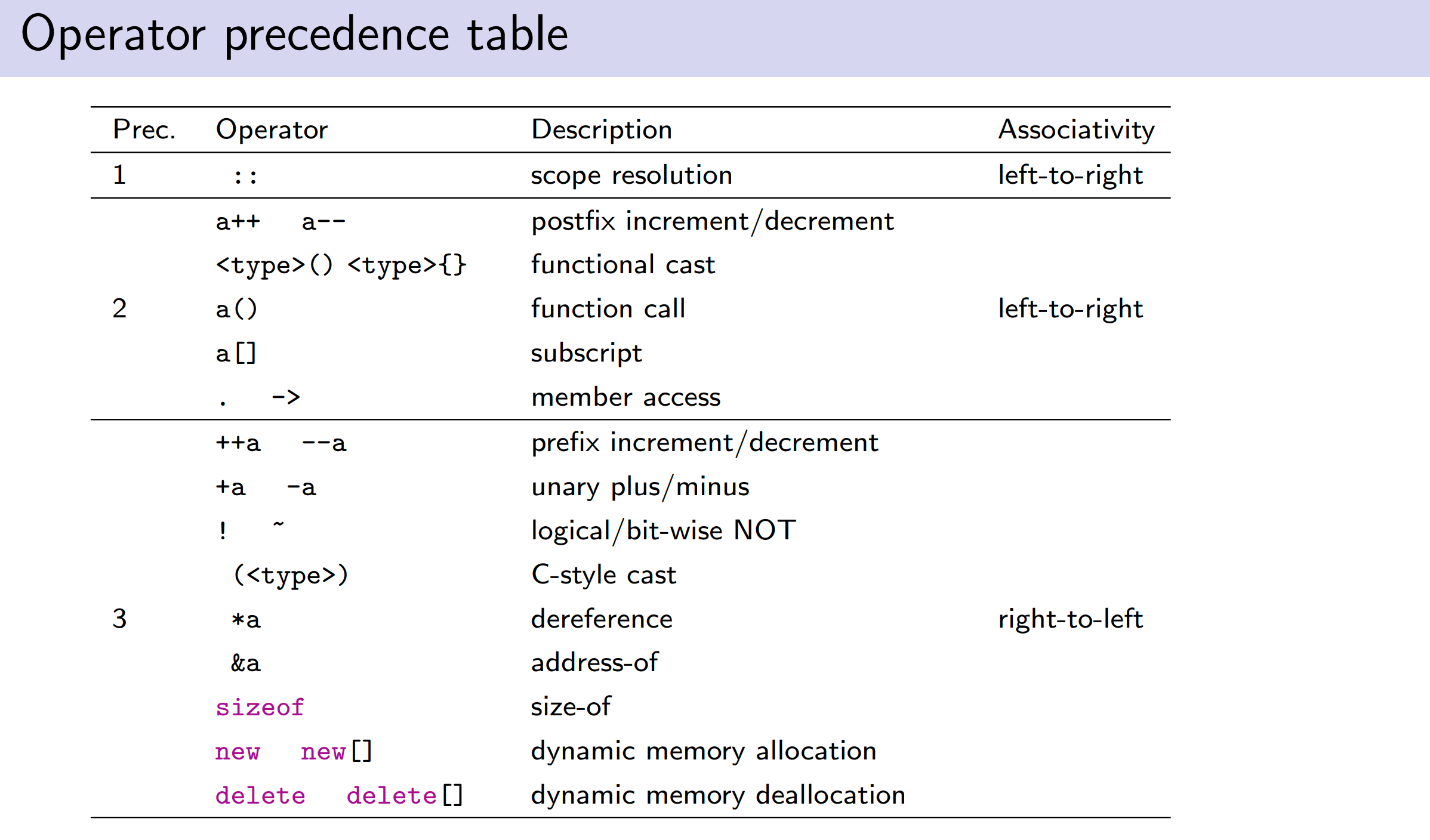

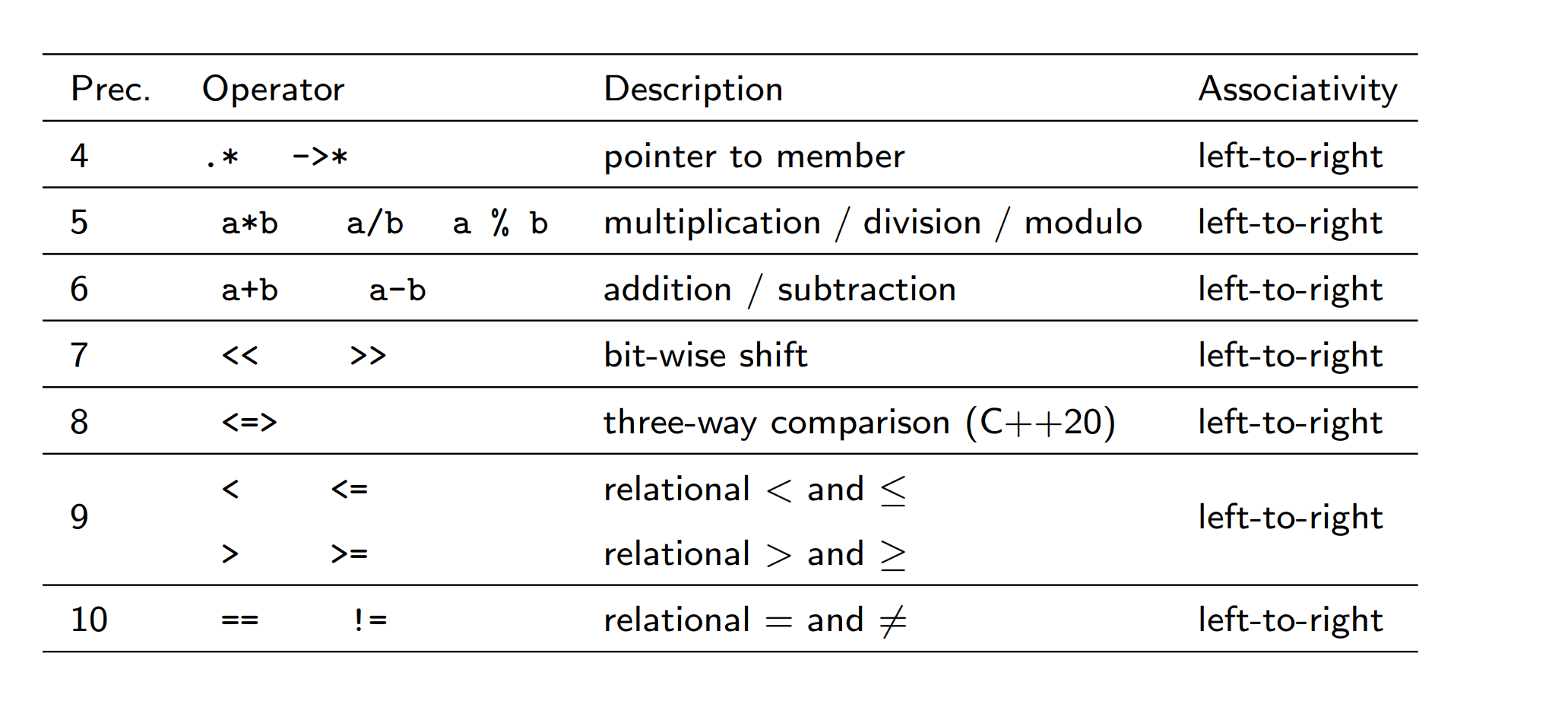

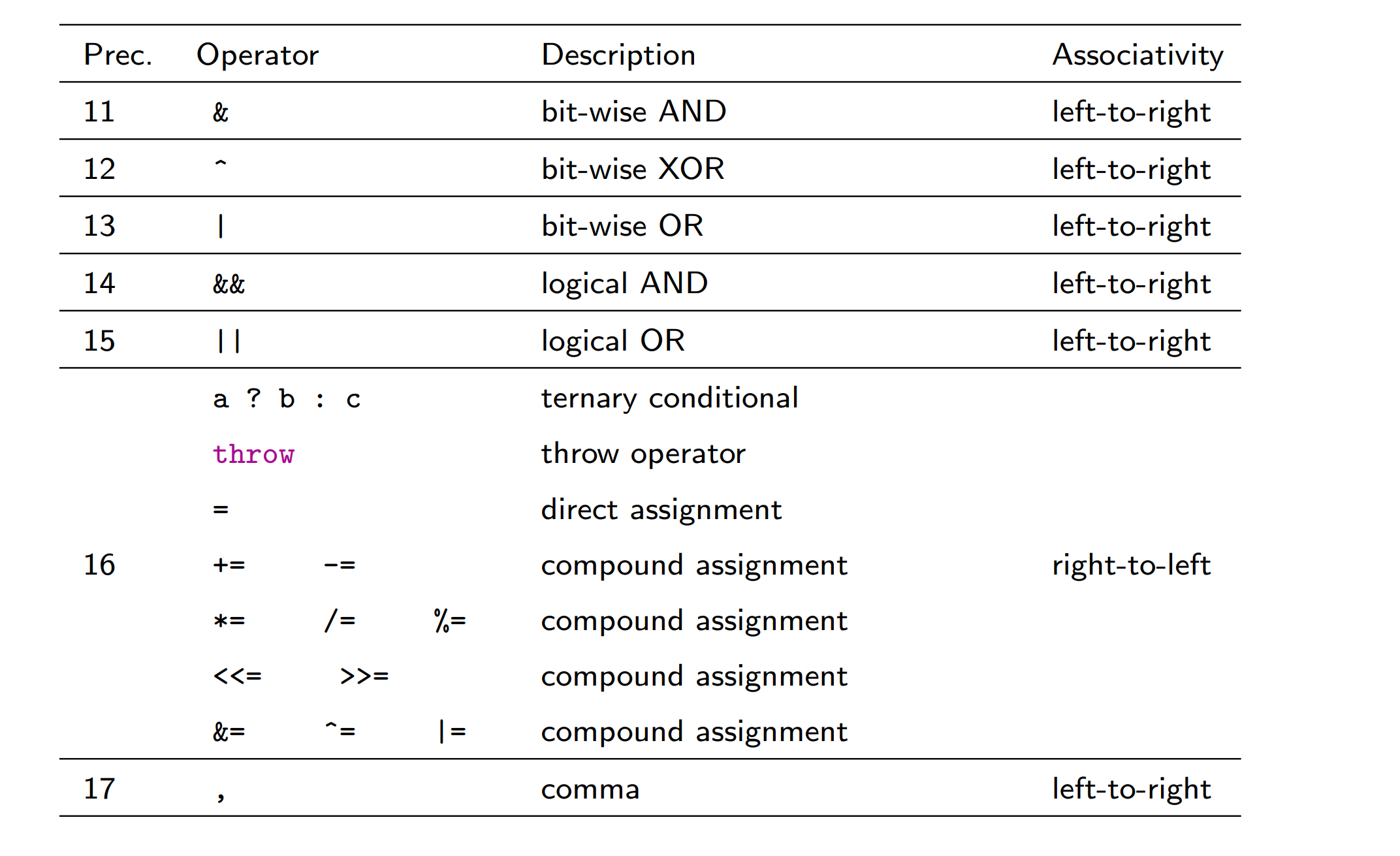

Precedence

-

operators with higher precedence bind tighter than operators with lower precedence

-

operators with equal precedence are bound in the direction of their associativity

if, switch

if (auto value{computeValue()}; value < 42) {

// do something

}

else {

// do something else

}

switch (computeValue()) {

case 21:

// do something if computeValue() was 21

break;

case 42:

// do something if computeValue() was 42

break;

default:

// do something if computeValue() was != 21 and != 42

break;

}

Reference

- LReference

&declarator - RReference

&&declarator

Refences are special

- there are no references to void

- references are immutable (although the referenced object can be mutable)

- references are not objects, i.e. they do not necessarily occupy storage

int &m{i}; // valid

int& n{i}; // also valid, by convention

- a reference to type T must be initialized to refer to a valid object

there are exceptions:function parameter declarations,function return type declarations,when using extern modifier

int global0{0};

int global1{0};

int& foo(unsigned which) {

if (!which)

return global0;

else

return global1;

}

int main() {

foo(0) = 42; // global0 == 42

foo(1) = 14; // global1 == 14

}

Rvalue references cannot (directly) bind to lvalues:

int i{10};

int&& j{i}; // ERROR: cannot bind rvalue ref to lvalue

int&& k{42}; // OK

Rvalue references can extend the lifetime of temporary objects:

int i{10};

int j{32};

int&& k{i + j}; // k == 42

k += 42; // k == 84

Overload resolution (see later) allows to distinguish between lvalues and rvalues:

void foo(int& x);

void foo(const int& x);

void foo(int&& x);

int& bar();

int baz();

int main() {

int i{42};

const int j{84};

foo(i); // calls foo(int&)

foo(j); // calls foo(const int&)

foo(123); // calls foo(int&&)

foo(bar()); // calls foo(int&)

foo(baz()); // calls foo(int&&)

}

references themselves cannot be const, however, the reference type can be const

Dangling references

int& foo() {

int i{42};

return i; // MISTAKE: returns dangling reference!

}

Converting

static cast:

static_cast< new_type > ( expression )

- new_type must have same const-ness as the type of expression

Do not use: (const_cast, reinterpret_cast, C-style cast: (new_type) expression)

int sum(int a, int b);

double sum(double a, double b);

int main() {

int a{42};

double b{3.14};

double x{sum(a, b)}; // ERROR: ambiguous

double y{sum(static_cast<double>(a), b)}; // OK

int z{sum(a, static_cast<int>(b))}; // OK

}

Function

C++ also allows a trailing return type:

auto foo() -> int;

template <typename T, typename U>

auto sum(const T& x, const U& y) -> decltype(x+y);

Return multiple

std::pair<int, std::string> foo() {

return std::make_pair(17, "C++");

}

std::tuple<int, int, float> bar() {

return std::make_tuple(1, 2, 3.0);

}

Structured Binding

std::map<std::string, int> myMap; // map with strings as keys

// ... fill the map ...

// iterate over the container using range-for loop

for (const auto& [key, value] : myMap)

std::println("{}: {}", key, value);

you can also bind struct members or std::array entries:

struct myStruct { int a{1}; int b{2}; };

auto [x, y] = myStruct{}; // x, y are int, x == 1, y == 2

std::array<int, 3> myArray{47, 11, 9};

auto [i, j, k] = myArray; // i == 47, j == 11, k == 9

specifying the return type for multiple values can be annoying:

auto bar() {

return std::make_tuple(1, 2, 3.0);

}

Parameter passing

- in parameter

void f1(const std::string& s); // OK, pass by const reference

void f2(std::string s); // potentially expensive

void f3(int x); // OK, cheap

void f4(const int& x); // not good, unnecessary overhead

in-outparameter

void update(Record& r); // assume that update writes to r

outparameter

return them

Overloading

the compiler automatically resolves the overloads in the current scope and calls the best match

void f(int); // a function called f, taking an int

void f(double); // another function f, taking a double

Criteria

- exact match. no or only trivial conversions, e.g. T to const T)

- match using promotions (e.g. bool to int, char to int, or float to double)

- match using standard conversions (e.g. int to double, double to int, or int to unsigned int)

- match using user-defined conversions

- match using ellipsis

void print(int);

void print(double);

void print(long);

void print(char);

void f(char c, int i, short s, float f) {

print(c); // exact match: print(char)

print(i); // exact match: print(int)

print(s); // integral promotion: print(int)

print(f); // float to double promotion: print(double)

print('a'); // exact match: print(char)

print(49); // exact match: print(int)

print(0); // exact match: print(int)

print(0L); // exact match: print(long)

}

using complex = std::complex<double>;

int pow(int, int);

double pow(double, double);

complex pow(double, complex);

complex pow(complex, int);

complex pow(complex, complex);

void h(complex z) {

auto i = pow(2, 2); // invokes pow(int, int)

auto d = pow(2.0, 2.0); // invokes pow(double, double)

auto z2 = pow(2, z); // invokes pow(double, complex)

auto z3 = pow(z, 2); // invokes pow(complex, int)

auto z4 = pow(z, z); // invokes pow(complex, complex)

auto e = pow(2.0, 2); // ERROR: ambiguous

}

Functors

Functions are not objects in C++

- they cannot be passed as parameters

- they cannot have state

However, a type T can be a function object (or functor), if:

- T is an object

- T defines

operator()

struct Adder {

int value{1};

int operator() (int param) {

return param + value;

}

};

int main() {

Adder adder;

adder(1); // 6

}

std::function is a wrapper for all callable targets

caution: can incur a slight overhead in both performance and memory

#include <functional>

int addFunc(int a) { return a + 3; }

int main() {

std::function adder{addFunc};

int a{adder(5)}; // a == 8

// alternatively specifying the function type:

std::function<int(int)> adder2{addFunc};

}

other example

#include <functional>

#include <iostream>

void printNum(int i) { std::println("{}", i); }

struct PrintNum {

void operator() (int i) { std::println("{}", i); }

};

int main() {

// store a function

std::function f_printNum{printNum};

f_printNum(-47);

// store the functor

std::function f_PrintNum{PrintNum{}};

f_PrintNum(11);

// fix the function parameter using std::bind

std::function<void()> f_leet{std::bind(printNum, 31337)};

f_leet();

}

Lambda

Lambda expressions are a simplified notation for anonymous function objects

std::find_if(container.begin(), container.end(),

[](int val) { return 1 < val && val < 10; }

);

- the function object created by the lambda expression is called closure

- the closure can hold copies or references of captured variables

[ capture_list ] ( param_list ) -> return_type { body }

-

capture_list specifies the variables of the environment to be captured in the closure

-

return_type specifies the return type; it is optional!

- if the param_list is empty, it can be omitted

Storing lambda

Lambda expressions can be stored in variables:

auto lambda = [](int a, int b) { return a + b; };

std::function func = [](int a, int b) { return a + b; };

std::function<int(int, int)> func2 =

[](int a, int b) { return a + b; };

std::println("{}", lambda(2, 3)); // outputs 5

- the type of a lambda expression is not defined, no two lambdas have the same type (even if they are identical otherwise)

auto myFunc(bool first) { // ERROR: ambiguous return type

if (first)

return []() { return 42; };

else

return []() { return 42; };

}

Capture

- all capture: by copy

=, by reference&

void f() {

int i{42};

auto lambda1 = [i]() { return i + 42; };

auto lambda2 = [&i]() { return i + 42; };

i = 0;

int a = lambda1(); // a == 84

int b = lambda2(); // b == 42

}

Exception

#include <stdexcept>

void foo(int i) {

if (i == 42)

throw 42;

throw std::logic_error("What is the meaning of life?");

}

- when an exception is thrown, C++ performs stack unwinding

ensures proper clean up of objects with automatic storage duration

#include <exception>

include <iostream>

void bar() {

try {

foo(42);

} catch (int i) {

/* handle the exception somehow */

} catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cerr << e.what() << "\n";

/* handle the exception somehow */

}

}

No except

int myFunction() noexcept; // may not throw an exception

- exceptions should be used rarely, main use case: establishing class invariants

- exceptions should not be used for control flow!

- some functions must not throw exceptions,

- destructors,move constructors and assignment operators

expected

std::expected<T,E> stores either a value of type T or an error of type E

has_value()checks if the expected value is therevalue()or*accesses the expected valueerror()returns the unexpected value-

monadic operations are also supported, such as

and_then()oror_else() -

performance guarantee: no dynamic memory allocation takes place

enum class parse_error { invalid_input };

auto parse_number(std::string_view str) -> std::expected<double, parse_error> {

if (str.empty())

return std::unexpected(parse_error::invalid_input);

// do actual parsing ...

return 0.0;

}

int main() {

auto process = [](std::string_view str) {

if (const auto num = parse_number(str); num.has_value())

std::println("value: {}", *num);

else if (num.error() == parse_error::invalid_input)

std::println("error: invalid input");

};

for (auto s : {"42", ""})

process(s);

}

std::expectedis well suited for more regular errors, such as errors in parsing- exception handling is well suited for the rare failures you cannot do much about at the called function (e.g. out of memory)

STL

optional

encapsulates a value that might or might not exist

std::optional<std::string> mightFail(int arg) {

if (arg == 0)

return std::optional<std::string>("zero");

else if (arg == 1)

return "one"; // equivalent to the case above

else if (arg < 7)

return std::make_optional<std::string>("less than 7");

else

return std::nullopt; // alternatively: return {};

}

mightFail(3).value(); // "less than 7"

mightFail(8).value(); // throws std::bad_optional_access

*mightFail(3); // "less than 7"

mightFail(6)->size(); // 11

mightFail(7)->empty(); // undefined behavior

check value

mightFail(3).has_value(); // true

mightFail(8).has_value(); // false

auto opt5 = mightFail(5);

if (opt5) // contextual conversion to bool

opt5->size(); // 11

default

mightFail(42).value_or("default"); // "default"

reset

auto opt6 = mightFail(6);

opt6.has_value(); // true

opt6.reset(); // clears the value

opt6.has_value(); // false

monadic operations

and_then: if optional has value, returns result of provided function applied to the value, else empty optionalor_else: if optional has value, return optional itself, otherwise result of provided functiontransformif optional has value, return optional with transformed value, else empty optional

std::optional<int> foo() { /* ... */ }

void bar() {

auto o = foo().or_else([]{ return std::optional{0}; })

.and_then([](int n) -> std::optional<int> { return n+1; })

.transform([](int n) { return n*2; })

.value_or(-1337);

std::println("{}", o);

}

Pair

std::pair<int, double> p1(123, 4.56);

p1.first; // == 123

p1.second; // == 4.56

auto p2 = std::make_pair(456, 1.23);

structure binding

auto t = std::make_tuple(123, 4.56);

auto [a, b] = t; // a is type int, b is type double

auto p = std::make_pair(4, 5);

auto& [x, y] = p; // x, y have type int&

x = 123; // p.first is now 123

variant

to store different alternative types in one object

std::variant<int, float> v;

v = 42; // v con tains int

int i = std::get<int>(v); // i is 42

try {

std::get<float>(v); // v contains int, not float; will throw

}

catch (const std::bad_variant_access& e) {

std::cerr << e.what() << "\n";

}

v = 1.0f;

assert(std::holds_alternative<float>(v)); // succeeds

assert(std::holds_alternative<int>(v)); // fails

apply different

struct SampleVisitor {

void operator() (int i) { std::println("int: {}", i); }

void operator() (float f) { std::println("float: {}", f); }

void operator() (const std::string& s) { std::println("string: {}", s); }

};

int main() {

std::variant<int, float, std::string> v;

v = 1.0f;

std::visit(SampleVisitor{}, v);

v = "Hello";

std::visit(SampleVisitor{}, v);

v = 7;

std::visit(SampleVisitor{}, v);

}

without struct, with overload pattern

template<class... Ts> struct overload : Ts... { using Ts::operator()...; };

int main() {

std::variant<int, float, std::string> v{"Goodbye"};

std::visit( overload{

[](int i) { std::println("int: {}", i); },

[](float f) { std::println("float: {}", f); },

[](const std::string& s) { std::println("string: {}", s); }

}, v);

}

String

std::string encapsulates character sequences

- manages its own memory (RAII)

- guaranteed contiguous memory storage

- since C++20, it has constexpr constructors

alias for std::basic_string<char>

std::string s{"Hello World!");

std::cout << s.at(4) << s[6] << "\n"; // prints "oW"

at() is bounds checked, [] is not, both return a reference

s.at(4) = 'x';

s[6] = 'Y';

std::cout << s << "\n"; // prints "Hellx Yorld!"

append()and +=: appends another string or character+concatenates stringsfindreturns offset of the first occurrence of the substring, or the constantstd::string::nposif not found

string view

provides a read-only view on already existing strings

substr()creates another string view in \(O(1)\)

std::string s{"garbage garbage garbage interesting garbage"};

std::string sub = s.substr(24, 11); // with string: O(n)

std::string_view s_view{s}; // with string_view: O(1)

std::string_view sub_view = s_view.substr(24, 11); // O(1)

// in place operations:

s_view.remove_prefix(24); // O(1)

s_view.remove_suffix(s_view.size() - 11); // O(1)

in fuction

// useful for function calls

bool isEqNaive(std::string a, std::string b) { return a == b; }

bool isEqWithViews(std::string_view a, std::string_view b) { return a == b; }

isEqNaive("abc", "def"); // 2 allocations at runtime

isEqWithViews("abc", "def"); // no allocation at runtime

Container

Vector

emplace bace

struct ExpensiveToCopy {

ExpensiveToCopy(int id, std::string comment)

: id_{id}, comment_{comment} {}

int id_;

std::string comment_;

};

std::vector<ExpensiveToCopy> vec;

// expensive

ExpensiveToCopy e1(, "my comment 1");

vec.push_back(e1);

// beter

vec.push_back(std::move(e1));

// best

vec.emplace_back(2, "my comment 2");

// also works at any other position:

auto it = vec.begin(); ++it;

vec.emplace(it, 3, "my comment 3");

reserve

std::vector<int> vec;

vec.reserve(1000000); // allocate space for 1000000 elements

vec.capacity(); // == 1000000

vec.size(); // == 0 (no elements stored yet!)

fit

std::vector<int> vec;

vec.reserve(100);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

vec.push_back(i);

// only needed a capacity of 10, free the space for the rest

vec.shrink_to_fit();

Other

std::arrayfor compile-time fixed-size arraysstd::dequeis a double-ended queuestd::listis a doubly-linked liststd::forward_listis a singly-linked liststd::queueprovides the typical queue interface, wrapping one of the sequence containers with appropriate functionsstd::stackprovides the typical stack interface, wrapping one of the sequence containers with appropriate functions (deque, vector, list)std::priority_queueprovides a typical priority interface, wrapping one of the sequence containers with random access (vector, deque)

unordered_map

unordered maps are associative containers of key-value pairs, keys are required to be unique

is internally a hash table

std::unordered_map<std::string, double> nameToGrade {{"maier", 1.3}, {"huber", 2.7}, {"lasser", 5.0}};

search

auto search = nameToGrade.find("maier");

if (search != nameToGrade.end()) {

// returns an iterator pointing to a pair

search->first; // == "maier"

search->second; // == 1.3

}

check exist

nameToGrade.count("blafasel"); // == 0

nameToGrade.contains("blafasel"); // == false (since C++20)

emplace

auto p = std::make_pair("mueller", 2.0);

nameToGrade.insert(p);

// or simpler:

nameToGrade.insert({"mustermann", 4.0});

// or emplace:

nameToGrade.emplace("gruber", 1.7);

remove

auto search = nameToGrade.find("lasser");

nameToGrade.erase(search); // remove pair with "lasser" as key

nameToGrade.clear(); // removes all elements

map

std::map<int, int> xToY {{1, 1}, {3, 9}, {7, 49}};

// returns an iterator to first greater element:

auto gt3 = xToY.upper_bound(3);

while (gt3 != xToY.end()) {

std::cout << gt3->first << "->" << gt3->second << "\n"; // 7->49

++gt3;

}

// returns iterator to first element not lower

auto geq3 = xToY.lower_bound(3); // 3->9 , 7->49

unordered set

- elements must not be modified! If an element’s hash changes, the container might become corrupted

Thread safety

- two different containers do not share state, i.e. all member functions can be called concurrently by different threads

- all const member functions can be called concurrently.

- iterator operations that only read (e.g. incrementing or dereferencing an iterator) can be run concurrently with reads of other iterators and const member functions

- different elements of the same container can be modified concurrently

rule of thumb: simultaneous reads on the same container are always OK, simultaneous read/writes on different containers are also OK. Everything else requires synchronization!

Iterator

different element access method for each container, i.e. container types not easily exchangeable in code

*end; // undefined behavior!

- range-for loop can also be used to iterate over a container; it requires the range expression to have a begin() and end() iterator

for (auto elem : vec)

std::cout << elem << ",";

// prints "one,two,three,four,"

Dynamic

for (it = vec.begin(); it != vec.end(); ++it) {

if (it->size() == 3) {

it = vec.insert(it, "foo");

// it now points to the newly inserted element

++it;

}

}

// vec == {"foo", "one", "foo", "two", "three", "four"}

for (it = vec.begin(); it != vec.end(); ) {

if (it->size() == 3) {

it = vec.erase(it);

// erase returns a new, valid iterator

// pointing to the next element

}

else

++it;

}

// vec == {"three", "four"}

- InputIterator and OutputIterator are the most basic iterators

- equality comparison: checks if two iterators point to the same position

- a dereferenced InputIterator can only be read

-

a dereferenced OutputIterator can only be written to

-

ForwardIterator combines InputIterator and OutputIterator

- BidirectionalIterator generalizes ForwardIterator

- RandomAccessIterator generalizes BidirectionalIterator

- additionally supports random access with

operator[] - ContiguousIterator guarantees that elements are stored in memory contiguously

- extends RandomAccessIterator

Ranges

#include <iostream>

#include <ranges>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::vector<int> numbers = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6};

auto results = numbers

| std::views::filter([](int n){ return n % 2 == 0; })

| std::views::transform([](int n){ return n * 2; });

for (auto v: results)

std::cout << v << " "; // outputs: 4 8 12

}

- a range is anything that can be iterated over

- i.e. it has to provide a begin() iterator and an end() sentinel

- a view is something that you apply to a range and which performs some operation

- a view does not own data

- time complexity to copy/move/assign is constant

- can be composed using the pipe symbol

| - views are lazily evaluated

#include <iostream>

#include <ranges>

bool isPrime(int i) { // not very efficient, but simple!

for (int j = 2; j*j <= i; ++j) {

if (i % j == 0) return false;

}

return true;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "20 prime numbers starting with 1'000'000:\n";

for (int i : std::views::iota(1'000'000)

| std::views::filter(isPrime)

| std::views::take(20) ) {

std::cout << i << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

Algorithm

- sort

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::vector<unsigned> v {3, 4, 1, 2};

std::sort(v.begin(), v.end(), [](unsigned lhs, unsigned rhs) {

return lhs > rhs;

}); // 4, 3, 2, 1

}

std::stable_sort- partially sorting a range:

std::partial_sort - check if a range is sorted:

std::is_sorted,std::is_sorted_until

Searching

unsorted:

find the first elements satisfying some criteria:

std::findstd::find_ifstd::find_if_not

search for a range

std::search

count match

std::countstd::count_if

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::vector<int> v {2, 6, 1, 7, 3, 7};

auto res1 = std::find(vec.begin(), vec.end(), 7);

int a = std::distance(vec.begin(), res1); // == 3

auto res2 = std::find(vec.begin(), vec.end(), 9);

assert(res2 == vec.end());

}

sorted

std::binary_search

lookup an element in sorted range [first, last), only checks for containment, therefore return type is bool

std::lower_bound

returns iterator pointing to the first element >= the search value

std::upper_bound

returns iterator pointing to first element > the search value

std::equal_range

returns pair of iterators (begin and end of range)

Permutation

initialize a dense range of elements:

std::iota

iterate over permutations in lexicographical order

std::next_permutationstd::prev_permutation

iota fills the range [first, last) with increasing values, starting at value

#include <numeric>

#include <memory>

int main() {

auto heapArray = std::make_unique<int[]>(5);

std::iota(heapArray.get(), heapArray.get() + 5, 2);

// heapArray is now {2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

}

More feature

std::minandstd::maxover a range instead of two elementsstd::mergeandstd::in_place_mergefor merging of sorted ranges- multiple set operations (intersection, union, difference, ...)

- heap functionality using

std::make_heap,std::push_heap,std::pop_heap - sampling of elements using

std::sample - swapping elements using

std::swap - range modifications:

std::copyto copy elements to a new locationstd::rotateto rotate a rangestd::shuffleto randomly reorder elements

Stream and IO

std::istream is the base class for input operations, alias for std::basic_istream<char>

std::ostream is the base class for output operations,

-

good(), fail(), bad(): checks if the stream is in a specific error state -

eof(): checks if the stream has reached end-of-file -

operator bool(): returns true if stream has no errors

input stream

get(): reads single or multiple characters until a delimiter is found

// defined by the standard library:

std::istream& operator>>(std::istream&, int&);

int value;

std::cin >> value;

// read (up to) 1024 chars from cin:

std::vector<char> buffer(1024);

std::cin.read(buffer.data(), 1024);

output stream

put(): writes a single character

// defined by the standard library:

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream&, int);

std::cout << 123;

// write 1024 characters to cout:

std::vector<char> buffer(1024);

std::cout.write(buffer.data(), 1024);

stringstream

std::stringstream can be used when input and output should be read and written from a std::string

std::stringstream stream("1 2 3");

int value;

stream >> value; // value == 1

stream.str("4"); // set stream contents to "4"

stream >> value; // value == 4

stream << "foo";

stream << 123;

stream.str(); // == "foo123"

filestream

std::ifstream input("input_file");

if (!input)

std::cout << "couldn't open input_file\n";

std::ofstream output("output_file");

if (!output)

std::cout << "couldn't open output_file\n";

// read an int from input_file and write it to output_file

int value{-1};

if (!(input >> value))

std::cout << "couldn't read from file\n";

if (!(output << value))

std::cout << couldn't write to file\n";

Caveats of streams

std::cout << std::format("{} {}: {}!\n", "Hello", "World", 2023);

since c++23

std::println("{} {}: {}!", "Hello", "World", 2023);

Object-oriented Programming

class_keyword is either class or struct

struct Foo {

int i{42};

std::string s{"Hello"};

std::vector<int> v; // not initialized

static int magicValue; // static member variable

};

Member function

struct Foo {

void foo(); // non-static member function

void cfoo() const; // const-qualified non-static member fct.

static void bar(); // static member function

Foo(); // constructor

~Foo(); // destructor

bool operator==(const Foo& f); // overloaded operator==

};

out line

struct Foo {

void foo1() { /* ... */ } // inline definition

void foo2();

void fooConst() const;

static void fooStatic();

};

// out-of-line definitions:

void Foo::foo2() { /* ... */ }

void Foo::fooConst() const { /* ... */ }

void Foo::fooStatic() { /* ... */ }

Access

struct C {

int i;

int foo() {

this->i; // explicit member access, 'this' is of type C*

return i; // implicit member access (preferred)

}

int foo() const {

return this->i; // 'this' is of type const C*

// preferred would be: return i;

}

};

the nested type has full access to the parent (friend, see later)

class

- class have default access private

- struct have default access public

class Foo {

int a; // a is private by default

public: // everything after this is public

int b;

int getA() const { return a; }

protected: // everything after this is protected

int c;

public: // everything after this is public

int ml{42};

};

Friend

- you can put friend declarations in the class body, granting the friend access to private and protected members of the class

friend function_declaration ;declaring a non-member function as friend of the class (with an implementation elsewhere)friend function_definition ;defines a non-member (!) function and declares it as friend of the classfriend class_specifier ;declares another class as friend of the class

class A {

int a;

friend class B; // class B is friend of A

friend void foo(A&); // non-member function foo is friend of A

friend void bar(A& a) { a.a = 42; }

// OK, non-member function bar is friend of A

};

class B {

friend class C; // class C is friend of B

void foo(A& a) { a.a = 42; } // OK, B is friend of A

};

class C {

void foo(A& a) { a.a = 42; } // ERROR, C is not friend of A

};

void foo(A& a) { a.a = 42; } // OK, foo is friend of A

classes can be forward declared: class_keyword name ;

this declares an incomplete type that will be defined later in the scope

const correctness

class A {

int i{42};

public:

int get() const { return i; } // const getter

void set(int j) { i = j; } // non-const setter

};

void foo (A& nonConstA, const A& constA) {

int a = nonConstA.get(); // OK

int b = constA.get(); // OK

nonConstA.set(11);// OK, non-const

constA.set (12); // ERROR: non-const method on const object

}

overload

struct Foo {

int getA() { return 1; }

int getA() const { return 2; }

int getB() const { return getA(); }

int getC() { return 3; }

};

Foo& foo = /* ... */;

const Foo& cfoo = /* ... */;

cfoo.getA() == 2, cfoo.getB() == 2, whilecfoo.getC()gives an error

Ref qualifier

struct Bar {

std::string s;

Bar(std::string t = "anonymous") : s{t} {} // constructor

void foo() & { std::println("{} normal instance", s); }

void foo() && { std::println("{} temporary instance", s); }

};

Bar b{"Fredbob"};

b.foo(); // prints "Fredbob normal instance"

Bar{}.foo(); // prints "anonymous temporary instance"

- if you use ref-qualifiers for a member function, all of its overloads need to have ref-qualifiers (cannot be mixed with normal overloads)

Static class member

struct Date {

int d, m, y;

static Date defaultDate;

void setDate(int dd = 0, int mm = 0, int yy = 0) {

d = dd ? dd : defaultDate.d;

m = mm ? mm : defaultDate.m;

y = yy ? yy : defaultDate.y;

}

// ...

static void setDefault(int dd, int mm, int yy) {

defaultDate = {dd, mm, yy};

}

};

Date Date::defaultDate{16, 12, 1770}; // definition of defaultDate

int main() {

Date d;

d.setDate(); // set to 16, 12, 1770

Date::setDefault(1, 1, 1900);

d.setDate(); // set to 1, 1, 1900

}

Constroctor and deconstructor

constructors consist of two parts:

- an initializer list (which is executed first)

- a regular function body (executed second)

struct A {

A() { std::cout << "Hello\n"; } // default constructor

};

struct B {

int a;

A b;

// default constructor implicitly defined by compiler

// does nothing for a, calls default constructor for b

};

struct Foo {

int a{123}; float b; const char c;

// default constructor with initializer list for b, c

Foo() : b{2.5}, c{7} {} // a has default initializer

// initializes a, b, c to the given values

Foo(int av, float bv, char cv) : a{av}, b{bv}, c{cv} {}

// delegate default constructor, then execute function body

Foo(float f) : Foo() { b *= f; }

};

- constructors with exactly one argument are special: they are used for implicit and explicit conversions

- if you do not want implicit conversion, mark the constructor as explicit

struct Foo {

Foo(int i);

};

struct Bar {

explicit Bar(int i);

};

void printFoo(Foo f) { /* ... */ }

void printBar(Bar b) { /* ... */ }

printFoo(123); // implicit conversion, calls Foo::Foo(int)

printBar(123); // ERROR: no implicit conversion

static_cast<Foo>(123); // explicit conversion, calls Foo::Foo(int)

static_cast<Bar>(123); // OK explicit conversion, calls Bar::Bar(int)

Copy constructorr

constructors of a class C that have a single argument of type C& or const C& (preferred) are called copy constructors

struct Foo {

Foo(const Foo& other) { /* ... */ } // copy constructor

};

void doStuff(Foo f) { /* ... */ }

int main() {

Foo f;

Foo g(f); // call copy constructor explicitly

doStuff(g); // call copy constructor implicitly

}

deconstructor

void f() {

Foo a;

{

Bar b;

// b.~Bar() is called

}

// a.~Foo() is called

}

Operator overloading

return_type operator op (arguments)

struct Int {

int i;

Int operator+() const { return *this; }

Int operator-() const { return Int{-i}; }

};

Int a{123};

+a; // equivalent to: a.operator+();

-a; // equivalent to: a.operator-();

binary

struct Int {

int i;

Int operator+(const Int& other) const {

return Int{i + other.i};

}

};

bool operator==(const Int&a, const Int& b) { return a.i == b.i; }

Int a{123}; Int b{456};

a + b; // equivalent to: a.operator+(b);

a == b; // equivalent to: operator==(a, b);

Increment

struct Int {

int i;

Int& operator++() { ++i; return *this; }

Int operator--(int) { Int copy{*this}; --i; return copy; }

};

Int a{123};

++a; // a.i is now 124

a++; // ERROR: post-increment not overloaded

Int b = a--; // b.i is 124, a.i is 123

--b; // ERROR: pre-decrement not overloaded

assignment

struct Int {

int i;

Int& operator=(const Int& other) { i = other.i; return *this; }

Int& operator+=(const Int& other) { i += other.i; return *this; }

};

Int a{123};

a = Int{456}; // a.i is now 456

a += Int{1}; // a.i is now 457

conversions

struct Int {

int i;

operator int() const { return i; }

};

Int a{123};

int x = a; // OK, x == 123

explicit

struct Float {

float f;

explicit operator float() const { return f; }

};

Float b{1.0};

float y = b; // ERROR, implicit conversion

float y = static_cast<float>(b); // OK, explicit conversion

Argument-dependent lookup

namespace A {

class X {};

X operator+(const X&, const X&) { return X{}; }

}

int main() {

A::X x, y;

A::operator+(x, y);

operator+(x, y); // ADL uses operator+ from namespace A

x + y; // ADL finds A::operator+() }

}

Enum class

- by default, the underlying type is an int

- by default, enumerator values are assigned increasing from 0

enum class TrafficLightColor {

red, yellow, green

};

RAII - Resource Acquisition is Initialization

bind the lifetime of a resource (e.g. memory, sockets, files, mutexes, database connections) to the lifetime of an object

Implementation:

- encapsulate each resource into a class whose sole responsibility is managing the resource

- the constructor acquires the resource and establishes all class invariants

- the destructor releases the resource

- typically, copy operations should be deleted and custom move operations need to be implemented (see later)

void writeMessage(std::string message) {

// mutex to protect file access across threads

static std::mutex myMutex;

// lock mutex before accessing file

std::lockguard<std::mutex> lock(myMutex);

std::ofstream file("message.txt"); // try to open file

if (!file.is_open()) // throw exception in case it failed

throw std::runtime_error("unable to open file");

file << message << "\n";

// no cleanup needed

// - file will be closed when leaving scope (regardless of

// exception) by ofstream destructor

// - mutex will be unlocked when leaving scope (regardless of

// exception) by lockguard destructor

}

Copy semantics

- construction and assignment of classes employs copy semantics in most cases

- by default, a shallow copy is created

Copy constructor

the copy constructor is invoked whenever an object is initialized from an object of the same type, its syntax is

class_name ( const class_name& )

the copy constructor is invoked for

- copy initialization:

T a = b; - direct initialization:

T a{b}; - function argument passing:

f(a);wherevoid f(T t) - function return:

return a;inside a functionT f();(if T has no move constructor, see later)

class A {

int v;

public:

explicit A(int v) : v{v} {}

A(const A& other) : v{other.v} {}

};

int main() {

A a1{42}; // calls A(int)

A a2{a1}; // calls copy constructor

A a3 = a2;// calls copy constructor

}

the compiler will implicitly declare a copy constructor if no user-defined copy constructor is provided

- the implicitly declared copy constructor will be a public member of the classthe implicitly declared copy constructor will be a public member of the class

- the implicitly declared copy constructor may or may not be defined!

the implicitly declared copy constructor is defined as = delete if one of the following is true:

- the class has non-static data members that cannot be copy-constructed

- the class has a base class which cannot be copy-constructed

- the class has a base class with a deleted or inaccessible destructor

- the class has a user-defined move constructor or move assignment operator

Copy assignment

the compiler will implicitly declare a copy assignment operator if no user-defined copy assignment operator is provided

the implicitly declared copy assignment operator is defined as = delete if one of the following is true:

- the class has non-static data members that cannot be copy-assigned

- the class has a base class which cannot be copy-assigned

- the class has a non-static data member of reference type

- the class has a user-defined move constructor or move assignment operator

if it is not deleted, the compiler defines the implicitly-declared copy constructor

- only if it is actually used

- it will perform a full member-wise copy of the object’s bases and members in their initialization order

- uses direct initialization

struct A {

const int v;

explicit A(int v) : v{v} {}

};

int main() {

A a1{42};

A a2{a1}; // OK: calls generated copy constructor

a1 = a2; // ERROR: the implicitly-declared copy assignment

// operator is deleted (as v is const)

}

often, a class should not be copyable anyway if the implicitly generated versions do not make sense

guidline:

- you should provide either provide both copy constructor and copy assignment, or neither of them

- the copy assignment operator should usually include a check to detect self-assignment

- if possible, resources should be reused; if resources cannot be reused, they have to be cleaned up properly

class A {

unsigned capacity;

std::unique_ptr<int[]> memory; // better would be: std::vector<int>

public:

explicit A(unsigned cap) : capacity{cap},

memory{std::make_unique<int[]>(capacity)} {}

A(const A& other) : A(other.capacity) {

std::copy(other.memory.get(), other.memory.get() + other.capacity, memory.get());

}

A& operator=(const A& other) {

if (this == &other) // check for self-assignment

return *this;

if (capacity != other.capacity) { // attempt resource reuse

capacity = other.capacity;

memory = std::make_unique<int[]>(capacity);

}

std::copy(other.memory.get(), other.memory.get() + other.capacity, memory.get());

return *this;

}

};

The Rule of Three

if a class requires one of the following, it almost certainly requires all three

- a user-defined destructor

- a user-defined copy constructor

- a user-defined copy assignment operator

Move Semantics

move constructor

- the move constructor is invoked when an object is initialized from an rvalue reference of the same type

class_name ( class_name&& ) noexcept

- the noexcept keyword is optional, but should be added to indicate that the move constructor never throws an exception

the function std::move from #include can be used to convert an lvalue to an rvalue reference

struct A {

A();

A(const A& other); // copy constructor

A(A&& other) noexcept; // move constructor

};

int main() {

A a1;

A a2(a1); // calls copy constructor

A a3(std::move(a1)); // calls move constructor

}

the move constructor for class type T and objects a,b is invoked for

- direct initialization:

T a{std::move(b)}; - copy initialization:

T a = std::move(b); - passing arguments to a function

void f(T t);viaf(std::move(a)) - returning from a function

T f();via return a;

Move assignment

the move assignment is invoked when an object appears on the left-hand side of an assignment with an rvalue reference on the right-hand side

class_name& operator=( class_name&& ) noexcept

the noexcept keyword is optional, but should be added to indicate that the move assignment never throws an exception

struct A {

A();

A(const A&); // copy constructor

A(A&&) noexcept; // move constructor

A& operator=(const A&); // copy assignment

A& operator=(A&&) noexcept; // move assignment

};

int main() {

A a1;

A a2 = a1; // calls copy constructor

A a3 = std::move(a1); // calls move constructor

a3 = a2; // calls copy assignment

a2 = std::move(a3); // calls move assignment

}

the compiler will implicitly declare a public move constructor, if all of the following conditions hold:

- there are no user-declared copy constructors

- there are no user-declared copy assignment operators

- there are no user-declared move assignment operators

- there are no user-declared destructors

the implicitly declared move constructor is defined as = delete if one of the following is true: \

- the class has non-static data members that cannot be moved

- the class has a base class which cannot be moved

- the class has a base class with a deleted or inaccessible destructor

the compiler will implicitly declare a public move assignment operator if all of the following conditions hold:

- there are no user-declared copy constructors

- there are no user-declared copy assignment operators

- there are no user-declared move constructors

- there are no user-declared destructors

the implicitly declared copy assignment operator is defined as = delete if one of the following is true:

- the class has non-static data members that cannot be moved

- the class has non-static data members of reference type

- the class has a base class which cannot be moved

- the class has a base class with a deleted or inaccessible destructor

if it is not deleted, the compiler defines the implicitly-declared move constructor

- only if it is actually used

- it will perform a full member-wise move of the object’s bases and members in their initialization order

- uses direct initialization

if it is not deleted, the compiler defines the implicitly-declared move assignment operator

- only if it is actually used

- it will perform a full member-wise move assignment of the object’s bases and members in their initialization order

- uses built-in assignment for scalar types and move assignment for class types

struct A {

const int v;

explicit A(int vv) : v{vv} {}

};

int main() {

A a1{42};

A a2{std::move(a1)}; // OK: calls generated move constructor

a1 = std::move(a2); // ERROR: the implicitly-declared move

// assignment operator is deleted

}

custom move constructors/assignment operators are often necessary

guideline:

- you should either provide both move constructor and move assignment, or neither of them

- the move assignment operator should usually include a check to detect self-assignment

- the move operations typically do not allocate new resources, but steal the resources from the argument

- the move operations should leave the argument in a valid (but indeterminate) state

- any previously held resources must be cleaned up properly!

class A {

unsigned capacity;

std::unique_ptr<int[]> memory; // better would be: std::vector<int>

public:

explicit A(unsigned cap) : capacity{cap},

memory{std::make_unique<int[]>(capacity)} {}

A(A&& other) noexcept : capacity{other.capacity},

memory{std::move(other.memory)} {

other.capacity = 0;

}

A& operator=(A&& other) noexcept {

if (this == &other) // check for self-assignment

return *this;

capacity = other.capacity;

memory = std::move(other.memory);

other.capacity = 0;

return *this;

}

}

The Rule of Five

- if a class wants move semantics, it has to define all five special member functions

- if a class wants only move semantics, it still has to define all five special member functions, but define the copy operations as

= delete

The Rule of Zero

- classes not dealing with ownership (e.g. of resources) should not have custom destructors, copy/move constructors or copy/move assignment operators

- classes that do deal with ownership should do so exclusively (and follow the Rule of Five)

Copy and swap

if copy assignment cannot benefit from resource reuse, the copy and swap idiom may be useful:

- the class only defines

class_name& operator=( class_name )copy-and-swap assignment operator

it acts as both copy and move assignment operator, depending on the value category of the argument

class A {

unsigned capacity;

std::unique_ptr<int[]> memory; // better would be: std::vector<int>

public:

explicit A(unsigned cap) : capacity{cap},

memory{std::make_unique<int[]>(capacity)} {}

A(const A& other) : A(other.capacity) {

std::copy(other.memory.get(),

other.memory.get() + other.capacity, memory.get());

}

A& operator=(A other) { // copy/move constructor will create 'other'

std::swap(capacity, other.capacity);

std::swap(memory, other.memory);

return *this;

} // destructor of 'other' cleans up resources formerly held by *this

};

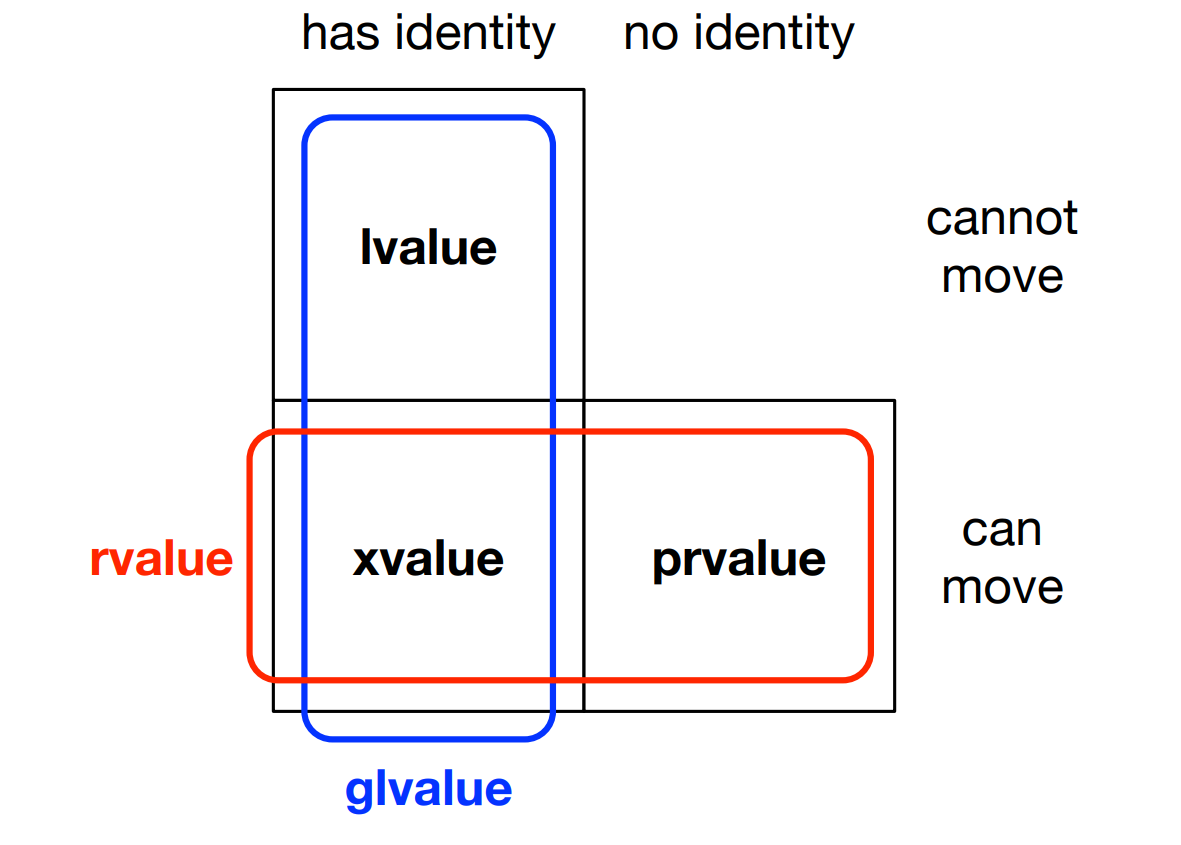

Copy elision(lvalue, rvalue)

-

glvalues identify objects

-

xvalues identify an object whose resources can be reused

int x;

f(std::move(x))

- prvalues compute the value of an operand or initialize an object

Compilers have to omit copy/move construction of class objects under certain circumstances:

- in a return statement, when the operand is a prvalue of the same class type as the function return type:

T f() {

return T();

}

f(); // only one call to default constructor of T

T x = T{T{f()}}; // only one call to default constructor of T

Ownership semantics

a resource should be owned (encapsulated) by exactly one object at all times, ownership can only be transferred explicitly by moving the respective object

- always use ownership semantics when managing resources in C++ (such as memory, file handles, sockets etc.)!

Smart pointer

unique pointer

-

std::unique_ptris a smart pointer implementing ownership semantics for arbitrary pointers -

assumes unique ownership of another object through a pointer

- automatically disposes of that object when

std::unique_ptrgoes out of scope - a

std::unique_ptrcan be used (almost) exactly like a raw pointer, but it can only be moved, not copied - a

std::unique_ptrmay be empty

ALWAYS use std::unique_ptr over raw pointers!

creation:

std::make_unique<type>(arg0, ..., argN)

- the

get()member function returns the raw pointer release()member function returns the raw pointer and releases ownership(very rarely required)

struct A{

int a;

int b;

A(int aa, int bb) : a{aa},b{bb} {}

};

void foo(std::unique_ptr<A> aptr) // assume ownership

// do sth

}

void bar(const A& a) { // does not assume ownership

/* do something */

}

int main() {

auto aptr = std::make_unique<A>(42,123);

int a = aptr->a;

bar(*aptr); // retain ownership

foo(std::move(aptr)) // transfer ownership

}

array example

std::unique_ptr<int[]> foo(unsigned size) {

auto buffer = std::make_unique<int[]>(size);

for (unsigned i = 0; i < size; ++i)

buffer[i] = i;

return buffer; // transfers ownership to caller

}

auto buffer = foo(42);

Advanced example

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#include <memory> // for std::make_unique

#include <type_traits> // for std::is_pointer_v

using namespace std;

#define _ <<" "<<

#define sz(x) ((int) (x).size())

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair<int, int> pii;

typedef vector<vector<int>> Graph;

typedef vector<vector<pair<int,ll>>> Graphl;

const int maxn = 5e5 + 5;

class A {

public:

int a = 1;

A() {}

virtual ~A() {} // required!

std::unique_ptr<A> clone() const {

return std::unique_ptr<A>(this->cloneImpl());

}

private:

virtual A* cloneImpl() const = 0;

};

template <typename Derived, typename Base>

class CloneInherit : public Base {

public:

std::unique_ptr<Derived> clone() const {

return std::unique_ptr<Derived>(

static_cast<Derived*>(this->cloneImpl()));

}

private:

virtual CloneInherit* cloneImpl() const override {

return new Derived(static_cast<const Derived&>(*this));

}

};

class B : public CloneInherit<B, A> {

// nothing to be done!

public:

int v = 1;

};

int main() {

auto b1 = make_unique<B>();

auto b2 = make_unique<B>();

b2->a = 1; b2->v = 2;

b1->a = 3; b1->v = 5;

// from B to A

unique_ptr<A> a1 = std::move(b1);

auto a2 = a1->clone();

// from A to B (2 kind)

B* t2 = dynamic_cast<B*>(a2.release());

unique_ptr<B> ut(dynamic_cast<B*>(a1.release()));

cout << t2->a _ t2->v << endl;

delete t2; // delete

return 0;

}

shared pointer

std::shared_ptr is a smart pointer implementing shared ownership

- a resource can be simultaneously shared with several owners

- the resource will only be released once the last owner releases it

- multiple

std::shared_ptrobjects can own the same raw pointer, implemented through reference counting - a

std::shared_ptrcan be copied and moved

use std::make_shared for creation

to break cycles, you can use std::weak_ptr

#include <memory>

#include <vector>

struct Node {

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Node>> children;

void addChild(std::shared_ptr<Node> child);

void removeChild(unsigned index);

};

int main() {

Node root;

root.addChild(std::make_shared<Node>());

root.addChild(std::make_shared<Node>());

root.children[0]->addChild(root.children[1]);

root.removeChild(1); // does not free memory yet

root.removeChild(0); // frees memory of both children

}

guidline:

std::unique_ptrshould almost always be passed by value- raw pointers represent resourcesraw pointers represent resources

- references grant temporary access to an object without assuming ownership

struct A { };

// reads a without assuming ownership

void readA(const A& a);

// may read and modify a but does not assume ownership

void readWriteA(A& a);

// works on a copy of A

void workOnCopyOfA(A a);

// assumes ownership of A

void consumeA(A&& a);

int main() {

A a;

readA(a);

readWrite(a);

workOnCopyOfA(a);

consumeA(std::move(a)); // cannot call without std::move

}

DO NOT DO:

int* i;

*i = 5; // OUCH: writing to random memory location

void f() {

int* i = new int{5};

// ... use i ...

} // OUCH: memory of i not freed, memory leak!

int* i = new int{5};

// ... use i ...

delete i;

delete i; // OUCH: freeing already freed pointer, undefined

void f(int* i) {

*i = 5; // OUCH: i might be nullptr

}

f(nullptr); // OUCH: this might crash or worse..

int *i = new int[5] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

int *j = i; // i and j now point to same location

*j = 10; // ok, i[0] is now 10

*j++ = 11; // ok, i[0] is now 11, j points to i[1]

*(++j) = 12; // ok, i[2] is now 12, j points to i[2]

*(j + 10) = 13; // OUCH: overwriting something unrelated to i/j

OOP2

Derived Class

any class type (struct or class) can be derived from one or several base classes

class class_name : base_specifier_list {

member_specification

};

base specifier list

access_specifier virtual_specifier base_class_name

example

class Base {

int a;

};

class Derived0 : public Base {

int b;

};

class Derived1 : private Base {

int c;

};

// multiple inheritance: avoid if possible

class Derived2 : public virtual Base, private Derived1 {

int d;

};

constructor

struct Base {

int a;

Base() : a{42} { std::cout << "Base::Base()\n"; }

explicit Base(int av) : a{av} {

std::cout << "Base::Base(int)\n";

}

};

struct Derived : Base {

int b;

Derived() : b{42} { std::cout << "Derived::Derived()\n"; }

Derived(int av, int bv) : Base(av), b{bv} {

std::cout << "Derived::Derived(int, int)\n";

}

};

int main() {

Derived derived0;

Derived derived1(123, 456);

}

// output

// Base::Base()

// Derived::Derived()

// Base::Base(int)

// Derived::Derived(int, int)

deconstructor

struct Base0 {

~Base0() { std::cout << "Base0::~Base0()\n"; }

};

struct Base1 {

~Base1() { std::cout << "Base1::~Base1()\n"; }

};

struct Derived : Base0, Base1 {

~Derived() { std::cout << "Derived::~Derived()\n"; }

};

int main() {

Derived derived;

}

// output

// Derived::~Derived()

// Base1::~Base1()

// Base0::~Base0()

qualified look up

struct A {

void a();

};

struct B : A {

void a();

};

int main {

B b;

b.a(); // calls B::a()

b.A::a(); // calls A::a()

}

inheritance mode

- public means the public base class members are public, and the protected members are protected

- protected means the public and protected base class members are only accessible for class members / friends of the derived class and its derived classes

- private means the public and protected base class members are only accessible for class members / friends of the derived class

Virtual function and polymorphy

inheritance in C++ is by default non-polymorphic, the type of the object determines which member is referred to

struct Base {

void foo() { std::cout << "Base::foo()\n"; }

};

struct Derived : Base {

void foo() { std::cout << "Derived::foo()\n"; }

};

int main() {

Derived d;

Base& b = d; // works, Derived IS-A Base

d.foo(); // prints Derived::foo()

b.foo(); // prints Base::foo()

}

virtual function

non-static member functions can be marked virtual, a class with at least one virtual function is polymorphic

- only the function in the base class needs to be marked virtual, the overriding functions in derived classes do not need to be (and should not be) marked

virtual - instead they are marked

override

struct Base {

virtual void foo() { std::cout << "Base::foo()\n"; }

};

struct Derived : Base {

void foo() override { std::cout << "Derived::foo()\n"; }

};

int main() {

Base b;

Derived d;

Base& br = b;

Base& dr = d;

d.foo(); // prints Derived::foo()

dr.foo(); // prints Derived::foo()

d.Base::foo(); // prints Base::foo()

dr.Base::foo(); // prints Base::foo()

br.foo(); // prints Base::foo()

}

with override

struct Base {

virtual void foo(int i);

virtual void bar();

};

struct Derived : Base {

void foo(float i) override; // ERROR: does not override foo(int)

void bar() const override; // ERROR: does not override bar()

};

to prevent overriding a function it can be marked as final:

struct Base {

virtual void foo() final;

};

struct Derived : Base {

void foo() override; // ERROR: overriding final function

};

struct Base final {

virtual void foo();

};

struct Derived : Base { // ERROR: deriving final class

void foo() override;

};

Virtual deconstructor

- derived objects can be deleted through a pointer to the base class, this leads to undefined behavior unless the destructor in the base class is virtual

- hence, the destructor in a base class should either be protected and non-virtual or public and virtual (this should be the default)

struct Base {

virtual ~Base() {}

};

struct Derived : Base { };

int main() {

Base* b = new Derived();

delete b; // OK thanks to virtual destructor

// but in general: don't use naked pointers/new/delete!

}

Slicing

inheritance hierarchies need to be handled via references (or pointers)!

struct A {

int x;

};

struct B : A {

int y;

};

void f() {

B b;

A a = b; // a will only contain x, y is lost

}

another example

struct A {

int x;

};

struct B : A {

int y;

};

void g() {

B b1;

B b2;

A& ar = b2;

ar = b1; // b2 now contains a mixture of b1 and b2!!!, x changed, y not change

}

in most of the cases you should then = delete all copy/move operations to prevent slicing

class BaseOfFive {

public:

virtual ~BaseOfFive() = default; // = {}

BaseOfFive(const BaseOfFive&) = delete;

BaseOfFive(BaseOfFive&&) = delete;

BaseOfFive& operator=(const BaseOfFive&) = delete;

BaseOfFive& operator=(BaseOfFive&&) = delete;

};

to enable copying of polymorphic objects, you can define a factory method

struct A {

A() {} // default constructor

virtual ~A() = default; // base class with virtual destructor

A(const A&) = delete; // prevent slicing

A(A&&) = delete;

A& operator=(const A&) = delete;

A& operator=(A&&) = delete;

virtual std::unique_ptr<A> clone () { return /* A object */; }

};

struct B : A {

std::unique_ptr<A> clone() override { return /* B object */; }

};

auto b = std::make_unique<B>();

auto a = b->clone(); // cloned copy of b

convert

to convert references (or pointers) in an inheritance hierarchy in a safe manner, you can use

dynamic_cast< new_type > ( expression )

example

struct A {

virtual ~A() = 0; // make class abstract

};

struct B : A{

void foo() const;

}

struct C : A{

void bar() const;

}

void baz(const A* aptr) {

if (auto bptr = dynamic_cast<const B*>(aptr)) {

bptr->foo();

} else if (auto cptr = dynamic_cast<const C*>(aptr)) {

cptr->bar();

}

}

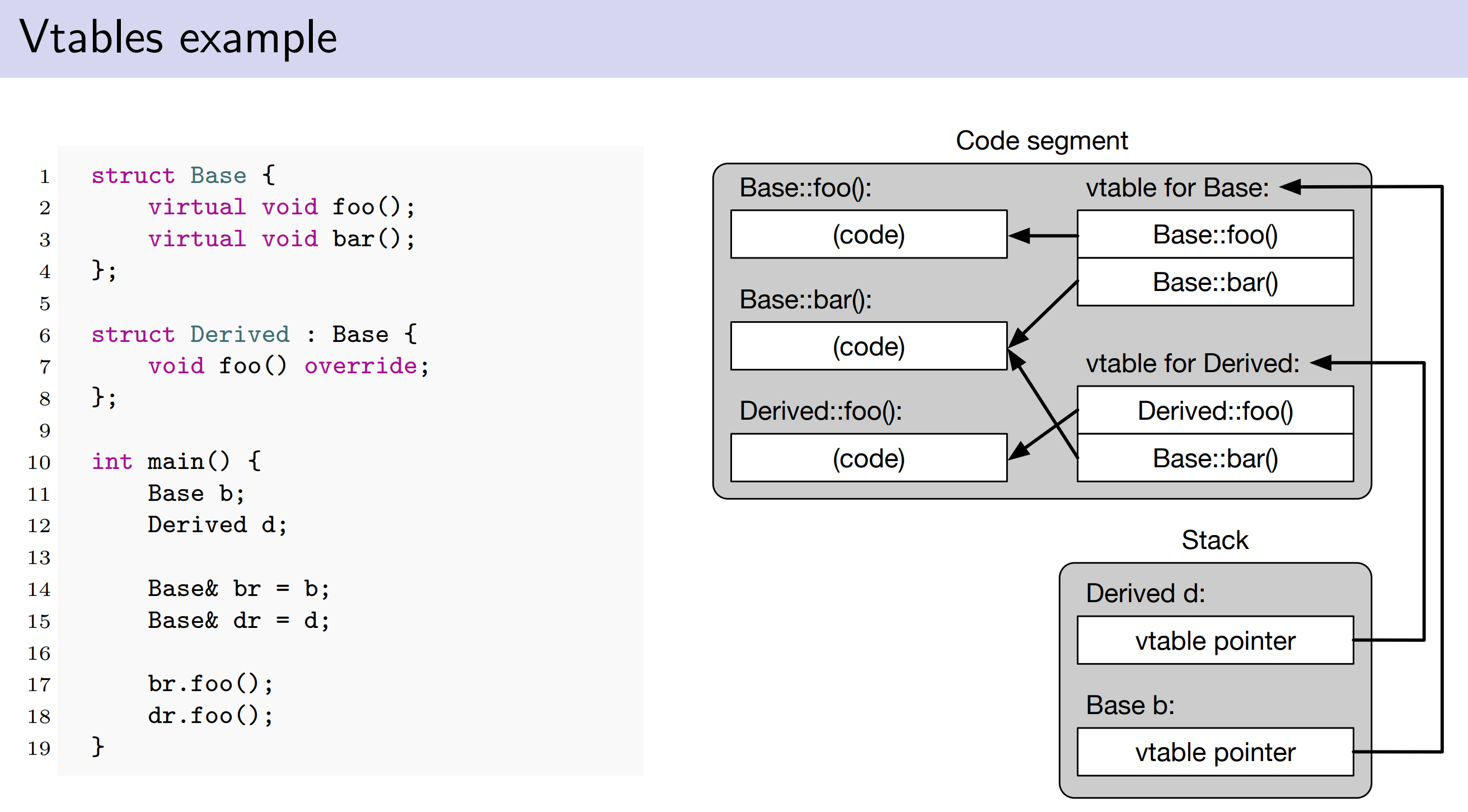

- polymorphism does not come for free, it has overhead! Implementation:vtable

- run-time cost,each virtual function call has to: follow the pointer to the vtable, follow the pointer to the actual function

- memory cost,polymorphic objects have larger size, as they have to store a pointer to the vtable

Pure virtual function

a virtual function can be marked as a pure virtual function by adding= 0at the end of the declarator/specifiers

abstract classes are special:

- they cannot be instantiated

- but they can be used as a base class (defining an interface)

-

references (and pointers) to abstract classes can be declared

-

caution: calling a pure virtual function in the constructor or destructor of an abstract class is undefined behavior!

The destructor can be marked as pure virtual

- useful when class needs to be abstract, but has no suitable functions that could be declared pure virtual

struct Base {

virtual ~Base() = 0;

};

Base::~Base() {}

int main() {

Base b; // ERROR: Base is abstract

}

shared from this

when you want to create std::shared_ptr of the class you are currently in, i.e. from this, you need to be careful

struct S : std::enable_shared_from_this<S> {

std::shared_ptr<S> notDangerous() { return shared_from_this(); }

};

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<S> sp1{std::make_shared<S>()};

std::shared_ptr<S> sp2 = sp1->notDangerous();

// all is good now!

}

caveat: this only works correctly if shared_from_this is called on an object that is already owned by a std::shared_ptr!

Concept of generic programming

template declaration syntax:

template < parameter_list > declaration

parameter_list is a comma-separated list of template parameters

- type template parameters

- non-type template parameters

- template template parameters

template <typename T, unsigned N>

class Array {

T storage[N];

public:

T& operator[](unsigned i) {

assert(i < N);

return storage[i];

}

};

template of template

template <template <class, unsigned> class ArrayType>

class Foo {

ArrayType<int, 42> someArray;

};

template parameters with default values cannot be followed by template parameters without default values

template arguments for template template arguments must name a class template or template alias

#include <array>

template <typename T, unsigned long N>

class MyArray { };

template <template <class, unsigned long> class Array>

class Foo {

Array<int, 42> bar;

};

int main() {

Foo<MyArray> foo1;

Foo<std::array> foo2;

}

alias template

namespace something::extremely::nested {

template <typename T, typename R>

class Handle { };

} // end namespace something::extremely::nested

template <typename T>

using Handle = something::extremely::nested::Handle<T, void*>;

int main() {

Handle<int> handle1;

Handle<double> handle2;

}

template instantiation

explicitly force instantiation of a template specialization

template class template_name < argument_list >;

template struct template_name < argument_list >;

template ret_type name < argument_list > (param_list); // function

example

template <typename T>

struct A {

T foo(T value) { return value + 42; }

T bar() { return 42; }

};

template <typename T>

T baz(T a, T b) {

return a * b;

}

// explicit instantiation of A<int>

template struct A<int>;

// explicit instantiation of baz<float>

template float baz<float>(float, float);

Implicit template instantiation:

template <typename T>

struct A {

T foo(T value) { return value + 42; }

T bar();

};

int main() {

A<int> a; // instantiates only A<int>

int x = a.foo(32); // instantiates A<int>::foo

// note: no error, even though A::bar is never defined

A<float>* aptr; // does not instantiate A<float>!

}

Out of line definition

template <typename T>

struct A {

T value;

A(T v);

template <typename R>

R convert();

};

template <typename T> // out-of-line definition

A<T>::A(T v) : value{v} {}

template <typename T>

template <typename R> // out-of-line definition

R A<T>::convert() { return static_cast<R>(value); }

Disambiguator

if such a name should be considered as a type, the typename disambiguator has to be used

struct A {

using MemberTypeAlias = float;

};

template <typename T>

struct B {

using AnotherMemberTypeAlias = typename T::MemberTypeAlias;

};

int main() {

B<A>::AnotherMemberTypeAlias value = 42.0f; // value is type float

}

if such a name should be considered as a template name, the template disambiguator has to be used

template <typename T>

struct A {

template <typename R>

R convert() { return static_cast<R>(42); }

};

template <typename T>

T foo() {

A<int> a;

return a.template convert<T>();

}

reference collapsing

template <typename T>

class Foo {

using Trref = T&&;

};

int main() {

Foo<int&&>::Trref x; // what is the type of x?

}

- rvalue reference to rvalue reference collapses to rvalue reference

- any other combination forms an lvalue reference

Template specialization

general

template <> declaration

example

template <typename T>

class MyContainer {

/* generic implementation */

};

template <>

class MyContainer<long> {

/* specific implementation for long */

};

int main() {

MyContainer<float> a; // uses generic implementation

MyContainer<long> b; // uses specific implementation

}

Partial specialization

template <typename C, typename T>

class SearchAlgorithm {

void find(const C& container, const T& value) {

/* do linear search */

}

};

template <typename T>

class SearchAlgorithm<std::vector<T>, T> {

void find(const std::vector<T>& container, const T& value) {

/* do binary search */

}

};

Template argument deduction

template <typename T>

void swap(T& a, T& b);

int main() {

int a{0};

int b{42};

swap(a, b); // T is deduced to be int

}

sometimes ambigouus

template <typename T>

T max(const T& a, const T& b);

int main() {

int a{0};

long b{42};

max(a, b); // ERROR: ambiguous deduction of T

max(a, a); // ok

max<int>(a, b); // ok

max<long>(a, b); // ok

}

class deduction

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::vector v1{42}; // vector<int> with one element

std::vector v2{v1}; // v2 is also vector<int>

// and not vector<vector<int>>

}

deduction guide

using namespace std::string_literals;

template <typename T1, typename T2>

struct MyPair {

T1 first;

T2 second;

MyPair(const T1& x, const T2& y) : first{x}, second{y} {}

};

// deduction guide for the constructor:

template <typename T1, typename T2>

MyPair(T1, T2) -> MyPair<T1, T2>;

int main() {

MyPair p1{"hi"s, "world"s}; // pair of std::string

}

stl

// let std::vector<> deduce element type from initializing iterators:

namespace std {

template <typename Iterator>

vector(Iterator, Iterator)

-> vector<typename iterator_traits<Iterator>::value_type>;

}

// this allows, for example:

std::set<float> s;

// ... fill s ...

std::vector v(s.begin(), s.end()); // OK, std::vector<float>

auto

auto does not require any modifiers to work, however, it can make code hard to understand and error prone, so all known modifiers should always be added to auto

const int* foo(); // using raw pointers for illustrative purposes only

int main() {

// BAD:

auto f1 = foo(); // auto is const int*

const auto f2 = foo(); // auto is int*

auto* f3 = foo(); // auto is const int

// GOOD:

const auto* f4 = foo(); // auto is int

}

auto is not deduced to a reference type,

this might incur unwanted copies, so always add all known modifiers to auto

struct A {

const A& foo() { return *this; }

};

int main() {

A a;

auto a1 = a.foo(); // BAD: auto is const A, copy

const auto& a2 = a.foo(); // GOOD: auto is A, no copy

}

template lambda

// generic lambda:

auto sumGen = [](auto x, auto y) { return x + y; };

// templated lambda:

auto sumTem = []<typename T>(T x, T y) { return x + y; };

in fact, since C++20, also ordinary functions can take auto parameters as well:

void f1(auto x) { /* ... */ }

this automatically translates into a function template with an invented template parameter for each auto parameter

Parameter pack

parameter packs are template parameters that accept zero or more arguments

- non-type:

type ... Args - type:

typename|class ... Args - template:

template < param_list > typename|class ... Args

// a variadic class template with one parameter pack

template <typename... T>

struct Tuple { };

// a variadic function template, expanding the pack in its argument

template <typename... T>

void printTuple(const Tuple<T...>& tuple);